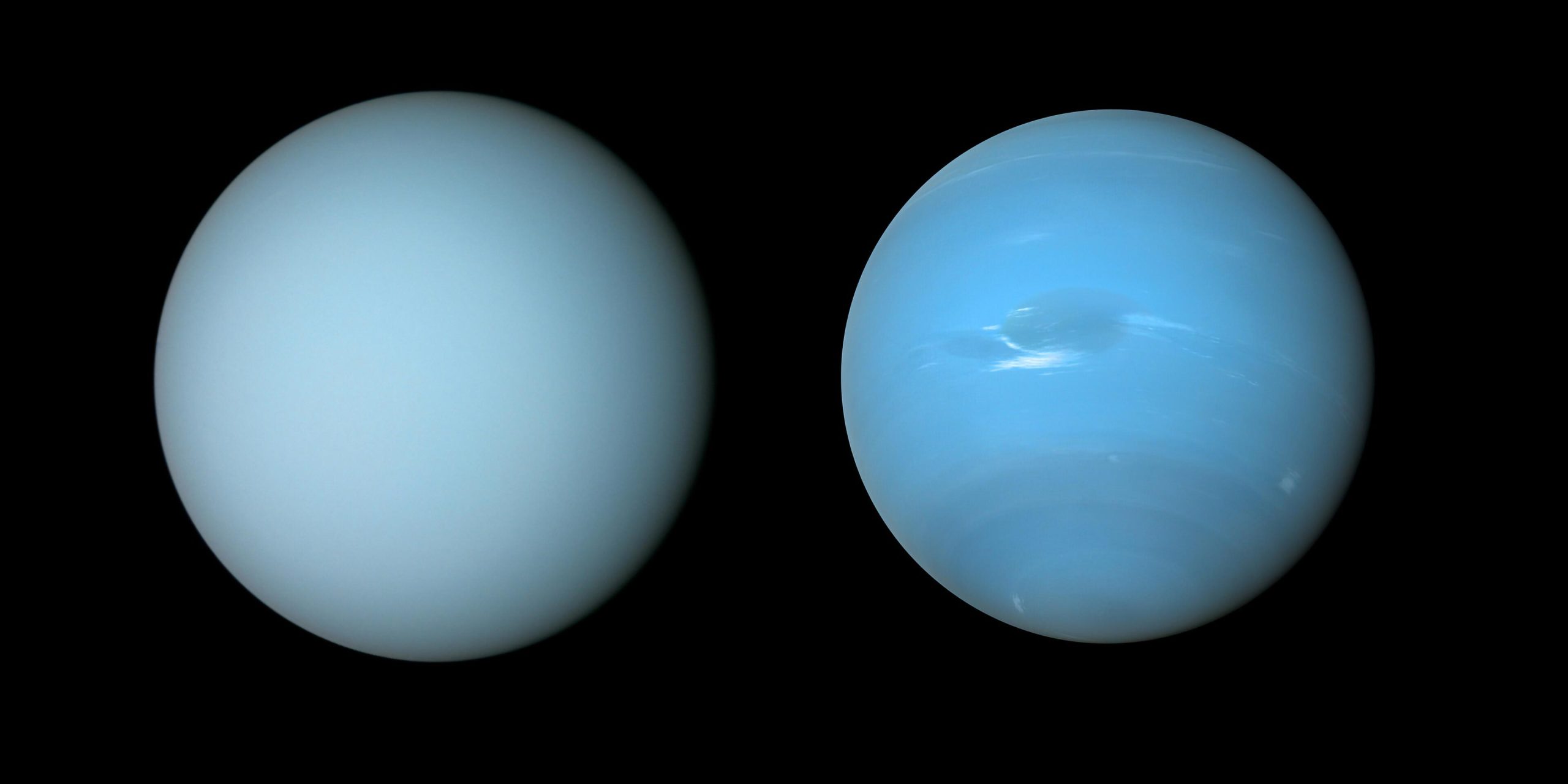

NASA’s Voyager 2-ruimtevaartuig legde deze beelden vast van Uranus (links) en Neptunus (rechts) tijdens planetaire flyby’s in de jaren tachtig. Krediet: NASA/JPL-Caltech/B. Johnson

Waarnemingen van het Gemini Observatorium en andere telescopen onthullen overmatige waas[{” attribute=””>Uranus makes it paler than Neptune.

Astronomers may now understand why the similar planets Uranus and Neptune have distinctive hues. Researchers constructed a single atmospheric model that matches observations of both planets using observations from the Gemini North telescope, the NASA Infrared Telescope Facility, and the Hubble Space Telescope. The model reveals that excess haze on Uranus accumulates in the planet’s stagnant, sluggish atmosphere, giving it a lighter hue than Neptune.

De planeten Neptunus en Uranus hebben veel gemeen – ze hebben vergelijkbare massa’s, afmetingen en atmosferische samenstellingen – maar hun uiterlijk is opmerkelijk verschillend. Op zichtbare golflengten is Neptunus zichtbaar blauwer van kleur, terwijl Uranus een lichtere tint cyaan heeft. Astronomen hebben nu een verklaring waarom de twee planeten zo verschillend van kleur zijn.

Nieuw onderzoek geeft aan dat de laag geconcentreerde waas die op beide planeten wordt gevonden, dikker is op Uranus dan een vergelijkbare laag op Neptunus en het uiterlijk van Uranus meer “witt” dan op Neptunus.[1] Als er geen mist in zit sfeer Vanaf Neptunus en Uranus zullen ze beide ongeveer gelijk in blauw verschijnen.[2]

Deze conclusie komt uit een model[3] dat een internationaal team onder leiding van Patrick Irwin, hoogleraar planetaire fysica aan de Universiteit van Oxford, heeft ontwikkeld om de aerosollagen in de atmosfeer van Neptunus en Uranus te beschrijven.[4] Eerdere onderzoeken naar de bovenste atmosferen van deze planeten waren gericht op het uiterlijk van de atmosfeer op specifieke golflengten. Dit nieuwe model, dat uit meerdere atmosferische lagen bestaat, komt echter overeen met waarnemingen van beide planeten over een breed scala aan golflengten. Het nieuwe model bevat ook vage deeltjes in diepere lagen waarvan eerder werd gedacht dat ze alleen wolken van methaan en waterstofsulfide-ijs bevatten.

Dit diagram toont drie lagen aerosolen in de atmosfeer van Uranus en Neptunus, zoals ontworpen door een team van wetenschappers onder leiding van Patrick Irwin. De hoogtemeter op de grafiek geeft de druk boven 10 bar weer.

De diepste laag (aërosollaag-1) is dik en bestaat uit een mengsel van waterstofsulfide-ijs en deeltjes afkomstig van de interactie van planetaire atmosferen met zonlicht.

De belangrijkste laag die de kleuren beïnvloedt, is de middelste laag, een laag mistdeeltjes (in het papier aangeduid als de aerosollaag-2) die dikker is op Uranus dan op Neptunus. Het team vermoedt dat op beide planeten methaanijs condenseert op de deeltjes in deze laag, waardoor de deeltjes dieper de atmosfeer in trekken als de methaansneeuw valt. Omdat de atmosfeer van Neptunus actiever en turbulenter is dan die van Uranus, gelooft het team dat de atmosfeer van Neptunus efficiënter is in het rangeren van methaandeeltjes in de nevellaag en het produceren van die sneeuw. Dit verwijdert meer waas en houdt de waaslaag van Neptunus dunner dan op Uranus, wat betekent dat het blauw van Neptunus sterker lijkt.

Boven beide lagen is een uitgebreide mistlaag (aërosollaag 3) vergelijkbaar met de laag eronder maar kwetsbaarder. Op Neptunus vormen zich boven deze laag ook grote methaanijsdeeltjes.

Krediet: Gemini International Observatory/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA, J. da Silva/NASA/JPL-Caltech/B. Johnson

“Dit is het eerste model dat synchroon past bij waarnemingen van gereflecteerd zonlicht van ultraviolet tot bijna-infrarood”, legt Irwin uit, hoofdauteur van een onderzoekspaper waarin deze bevinding wordt gepresenteerd in de Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. “Hij is ook de eerste die het verschil in zichtbare kleur tussen Uranus en Neptunus verklaart.”

Het model van het team bestaat uit drie lagen aerosolen op verschillende hoogtes.[5] De belangrijkste laag die de kleuren beïnvloedt, is de middelste laag, een laag mistdeeltjes (in het papier de aerosollaag-2) die dikker is over de Uranus Van de Neptunus. Het team vermoedt dat op beide planeten methaanijs condenseert op de deeltjes in deze laag, waardoor de deeltjes dieper de atmosfeer in trekken als de methaansneeuw valt. Omdat de atmosfeer van Neptunus actiever en turbulenter is dan die van Uranus, gelooft het team dat de atmosfeer van Neptunus efficiënter is in het rangeren van methaandeeltjes in de nevellaag en het produceren van die sneeuw. Dit verwijdert meer waas en houdt de waaslaag van Neptunus dunner dan op Uranus, wat betekent dat het blauw van Neptunus sterker lijkt.

Mike Wong, een astronoom bij[{” attribute=””>University of California, Berkeley, and a member of the team behind this result. “Explaining the difference in color between Uranus and Neptune was an unexpected bonus!”

To create this model, Irwin’s team analyzed a set of observations of the planets encompassing ultraviolet, visible, and near-infrared wavelengths (from 0.3 to 2.5 micrometers) taken with the Near-Infrared Integral Field Spectrometer (NIFS) on the Gemini North telescope near the summit of Maunakea in Hawai‘i — which is part of the international Gemini Observatory, a Program of NSF’s NOIRLab — as well as archival data from the NASA Infrared Telescope Facility, also located in Hawai‘i, and the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope.

The NIFS instrument on Gemini North was particularly important to this result as it is able to provide spectra — measurements of how bright an object is at different wavelengths — for every point in its field of view. This provided the team with detailed measurements of how reflective both planets’ atmospheres are across both the full disk of the planet and across a range of near-infrared wavelengths.

“The Gemini observatories continue to deliver new insights into the nature of our planetary neighbors,” said Martin Still, Gemini Program Officer at the National Science Foundation. “In this experiment, Gemini North provided a component within a suite of ground- and space-based facilities critical to the detection and characterization of atmospheric hazes.”

The model also helps explain the dark spots that are occasionally visible on Neptune and less commonly detected on Uranus. While astronomers were already aware of the presence of dark spots in the atmospheres of both planets, they didn’t know which aerosol layer was causing these dark spots or why the aerosols at those layers were less reflective. The team’s research sheds light on these questions by showing that a darkening of the deepest layer of their model would produce dark spots similar to those seen on Neptune and perhaps Uranus.

Notes

- This whitening effect is similar to how clouds in exoplanet atmospheres dull or ‘flatten’ features in the spectra of exoplanets.

- The red colors of the sunlight scattered from the haze and air molecules are more absorbed by methane molecules in the atmosphere of the planets. This process — referred to as Rayleigh scattering — is what makes skies blue here on Earth (though in Earth’s atmosphere sunlight is mostly scattered by nitrogen molecules rather than hydrogen molecules). Rayleigh scattering occurs predominantly at shorter, bluer wavelengths.

- An aerosol is a suspension of fine droplets or particles in a gas. Common examples on Earth include mist, soot, smoke, and fog. On Neptune and Uranus, particles produced by sunlight interacting with elements in the atmosphere (photochemical reactions) are responsible for aerosol hazes in these planets’ atmospheres.

- A scientific model is a computational tool used by scientists to test predictions about a phenomena that would be impossible to do in the real world.

- The deepest layer (referred to in the paper as the Aerosol-1 layer) is thick and is composed of a mixture of hydrogen sulfide ice and particles produced by the interaction of the planets’ atmospheres with sunlight. The top layer is an extended layer of haze (the Aerosol-3 layer) similar to the middle layer but more tenuous. On Neptune, large methane ice particles also form above this layer.

More information

This research was presented in the paper “Hazy blue worlds: A holistic aerosol model for Uranus and Neptune, including Dark Spots” to appear in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets.

The team is composed of P.G.J. Irwin (Department of Physics, University of Oxford, UK), N.A. Teanby (School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, UK), L.N. Fletcher (School of Physics & Astronomy, University of Leicester, UK), D. Toledo (Instituto Nacional de Tecnica Aeroespacial, Spain), G.S. Orton (Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, USA), M.H. Wong (Center for Integrative Planetary Science, University of California, Berkeley, USA), M.T. Roman (School of Physics & Astronomy, University of Leicester, UK), S. Perez-Hoyos (University of the Basque Country, Spain), A. James (Department of Physics, University of Oxford, UK), J. Dobinson (Department of Physics, University of Oxford, UK).

NSF’s NOIRLab (National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory), the US center for ground-based optical-infrared astronomy, operates the international Gemini Observatory (a facility of NSF, NRC–Canada, ANID–Chile, MCTIC–Brazil, MINCyT–Argentina, and KASI–Republic of Korea), Kitt Peak National Observatory (KPNO), Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (CTIO), the Community Science and Data Center (CSDC), and Vera C. Rubin Observatory (operated in cooperation with the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory). It is managed by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA) under a cooperative agreement with NSF and is headquartered in Tucson, Arizona. The astronomical community is honored to have the opportunity to conduct astronomical research on Iolkam Du’ag (Kitt Peak) in Arizona, on Maunakea in Hawai‘i, and on Cerro Tololo and Cerro Pachón in Chile. We recognize and acknowledge the very significant cultural role and reverence that these sites have for the Tohono O’odham Nation, the Native Hawaiian community, and the local communities in Chile, respectively.

‘Webgeek. Wannabe-denker. Lezer. Freelance reisevangelist. Liefhebber van popcultuur. Gecertificeerde muziekwetenschapper.’